2024. 10. 20. 04:13ㆍWonderful World

Discovered by the Dutch in 1722, Easter Island was first named Paaseiland (translated as "Easter Island") and was taken over by Chile in 1888.

The island has a total area of 163,6 km2 (63,2 mi2) and population around 6,600. The nearest inhabited land is Pitcairn Island, at approx 2075 km (1290 mi) to the west. The nearest town is Rikitea (on Mangareva Island, Gambier Islands, French Polynesia, population around 500) located approx 2606 km (1620 mi) to the west.

Islanders are referred to as pascuense (in Spanish). However, it's common to refer to the members of the indigenous community as "Rapa Nui".

Besides tourism (including by cruise ship passengers), the island's other businesses are commercial fishing and farming.

Easter Island is served by the Mataveri Airport. LAN Airlines (domestic airline) offers regular and direct flights to Santiago Chile, Papeete (Tahiti, French Polynesia) and Lima (Peru).

There is a marine shipping service to Valparaiso port (Santiago, Chile).

Hanga Roa is the island's port town with population around 3,500 (~90% of the total population). The town features the Avenida Atamu Tekena avenue, lined up with many guesthouses, hostels and luxury hotels (total capacity around 600 beds), stores restaurants, internet cafes. The town also features a museum, a Roman Catholic church, a multi-use stadium, Estadio de Hanga Roa, which is the home ground of the Easter Island football team.

Wood was scarce on the island during the 18th-19th centuries, but several highly detailed and distinctive carvings found their way to world-famous museums.

In 1995, Easter Island was designated a UNESCO Site, with much of its territory protected within Rapa Nui National Park.

RANO RARAKU - The moai statue quarry

Travels in Geology: Easter Island's enduring enigmas

by Terri Cook and Lon Abbott

Thursday, March 23, 2017

After being knocked down by a tsunami in 1960, the 15 moai perched on Ahu Tongariki were restored a few decades later. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

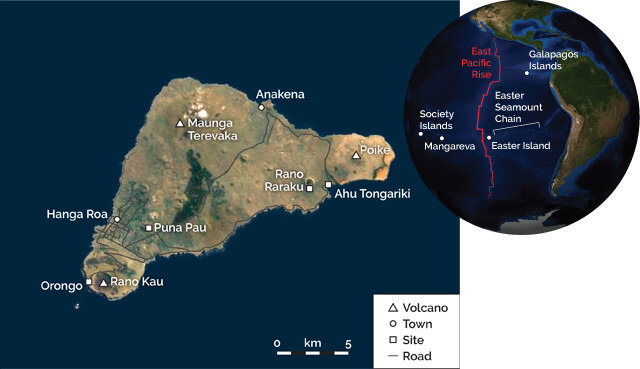

Few destinations are as steeped in mystique as Easter Island. Located in the southeastern Pacific nearly 3,700 kilometers west of Chile, and more than 2,000 kilometers from the nearest inhabited land, Easter Island is one of the most isolated places on the planet. The lonely isle is renowned for its remarkable moai — massive stone carvings of human-like figures with oversized heads — that for centuries have stood watch over this small speck of land. The moai’s original purpose, as well as the means by which they were transported and erected, remains shrouded in mystery; for some, the figures' eternal stares have come to symbolize societal collapse due to environmental degradation, although the details of the theory behind this view have been vigorously contested. Also controversial, at least among geologists, is the origin story of the island itself and whether or not it was formed by a hot spot. While planning a recent trip to Chile, we couldn’t resist the opportunity to visit Easter Island’s storied shores and experience these enduring enigmas first-hand.

Hot Line or Hot Spot?

Easter Island is a volcanic island located a few hundred kilometers east of the planet's fastest oceanic spreading center. Credit: both: K. Cantner, AGI.

Easter Island, which at 164 square kilometers is slightly smaller than the District of Columbia, is an amalgamation of three volcanoes that erupted between about 780,000 and 110,000 years ago. The island lies near the western end of a 2,500-kilometer-long chain of underwater volcanoes called the Easter Seamount Chain that resembles the classic Hawaiian hot spot track, which is thought to have formed as the Pacific Plate slowly drifted across a persistent upwelling of hot material from deep within the mantle. Yet, unlike the Hawaiian Islands, whose ages steadily rise with increasing distance from the active volcanoes, the Easter Seamount Chain has no clear age progression, with very young volcanoes spanning more than 500 kilometers of its length.

Easter Island is just a few hundred kilometers east of the southern East Pacific Rise spreading center, so it sits on young oceanic crust that’s just 2 million to 4 million years old. But the island’s volcanoes are younger still, so the island couldn’t have formed simply from mid-ocean ridge volcanism. Researchers have proposed many alternative hypotheses to explain the seamount chain, including that it’s a manifestation of a new plate boundary; that it sits atop a “leaky” transform fault; or that the chain, from Easter Island to Sala y Gómez Island 400 kilometers to the east, results from volcanism from a long, thin mantle “hot line” instead of a typical hot spot.

Coastal erosion that has bitten into the Poike Volcano on the island's northeastern side has created the dramatic sea cliffs that frame these moai. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

The island’s proximity to the East Pacific Rise, which is spreading at a rate of 15 centimeters per year — making it the fastest spreading ridge in the world — has caused other scientists to argue that Easter Island was formed by a traditional hot spot that behaved in an untraditional way. They argue that the actual hot spot lies under the equally young Sala y Gómez Island, but that hot spot magma is drawn toward the mid-ocean ridge in a subterranean channel, where the magma from the hot spot mixes with mid-ocean ridge magma to produce Easter Island’s volcanoes.

Although the specifics of Easter Island’s origin remain elusive, the geochemistry of its volcanoes indicates that it is associated with some form of hot spot. Whichever way the magma makes it to the surface, it does so in small batches, with a rate of production more than 1,000 times slower than at Hawaii, possibly because the East Pacific Rise siphons much of the magma away from Easter Island.

What Happened on Rapa Nui?

Although the earliest European explorers recorded standing moai, all of the statues had toppled by the mid-19th century. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Known as Rapa Nui to the native Polynesian inhabitants, Easter Island is more commonly known by the name that Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen bestowed when he encountered it on Easter Sunday in 1722. When Roggeveen arrived, he estimated that the island hosted several thousand inhabitants and reported seeing standing moai, as did other explorers later that century. By the mid-19th century, however, all of the statues had reportedly toppled over.

According to prevailing archaeological interpretations, the moai represent the ancestors of the original colonizers, who likely voyaged there — a trip of at least 2,000 kilometers, and perhaps as much as 3,600 kilometers — from southeastern Polynesia in open canoes. When, exactly, they made this trip is as puzzling as the island’s origin; the fifth-century A.D. timing originally proposed by archaeologists was later modified to about A.D. 800, but the most recent work suggests colonization didn’t occur until about 1200. Although it’s uncertain when exactly the islanders began to create moai, their production lasted until the 17th century and resulted in nearly 900 statues, including many that were never finished.

Why the islanders stopped carving moai after the 17th century has been the subject of heated debate. Both archaeological evidence and fossil pollen data indicate that the island became deforested about the time that people stopped carving them. Researchers have used this observation to argue that anthropogenic deforestation led to soil degradation and wholesale ecological catastrophe, which in turn caused societal collapse.

Early inhabitants carved ceremonial petroglyphs into the island's dark basalt. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

As such, Easter Island has entered popular consciousness as a warning to the world about the potentially catastrophic consequences of rampant resource exploitation. In his book “Collapse,” UCLA geographer Jared Diamond argues that overexploitation of the island’s limited resources, particularly trees, led to warfare between rival tribes, sealing the culture’s demise. In another hypothesis, however, University of Hawaii anthropologist Terry Hunt blames Rapa Nui’s ecosystem collapse on the introduction of invasive Polynesian rats.

Researchers also disagree about the size of the island’s population. Diamond contends that it once reached a peak of about 15,000 people, but then crashed to perhaps just a few thousand prior to European contact. Hunt, meanwhile, says that the island’s population likely reached a maximum of roughly 3,000 by A.D. 1350 and then remained about that size until the arrival of Roggeveen, after which the population decreased again.

Still other researchers suggest natural climate change may have caused deforestation on the island. Analyses of pollen in a sediment core taken from Rano Raraku Lake indicate that vegetation shifted rapidly and repeatedly over the last 34,000 years as the island’s climate fluctuated. Palm trees became scarce during cool, wet periods such as the one that prevailed during the Little Ice Age, which was in full swing at the time moai carving ceased and the society purportedly collapsed. Here too, Easter Island presents visitors with an enigma to ponder: Does this island’s history offer a warning about the dangers of resource overexploitation, the consequences of climate change, or both?

Mysterious Moai

A record of Easter Island's changing flora was derived from sediment cores extracted from the lake nestled in the Rano Raraku crater. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Seeing the remarkable moai is the highlight of any visit to Easter Island. With just a few exceptions, the statues sit atop large stone platforms (called ahus) located along the coast. As if they were watching over their descendants, all but a few moai face inland, with their backs daringly facing the sea. Most of the moai are protected within the borders of Rapa Nui National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site that covers roughly 40 percent of the island. Moais vary in size, ranging from 1 to 10 meters high, and weighing up to 82 tons.

The first statues that most visitors see are a couple of small congregations on the outskirts of Hanga Roa, the isle’s only settlement, where nearly all 5,800 residents live. The most notable of these are slightly north of town, where three ahus are perched on a dark basaltic cliff above the clear blue sea. One hosts the remains of five moai, while another holds just one; the latter sports eyeballs and a reddish cylindrical stone called a pukao, or topknot, set atop it. Pukao adorn many of the statues and may represent a male hairstyle once common on the island.

The moais' bright red topknots were carved from the Puna Pau scoria quarry located on the outskirts of Hanga Roa. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Dozens of other ahus are scattered around Easter Island. All are worth visiting, but the most impressive is Ahu Tongariki, which hosts 15 towering moai in a spectacular seaside setting on the island’s east coast with Poike, one of the island’s three major volcanic cones, looming behind. In 1960, the Great Chilean Earthquake — the most powerful earthquake ever recorded — produced a tsunami that swept some of the island’s largest moai 1.5 kilometers inland. Fortunately for modern-day visitors, a team of Japanese archaeologists moved the statues back to their original spots a few decades later.

Crater of the Moai

The moai were carved from lightweight volcanic breccia erupted from the Rano Raraku crater. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

On a hill west of Ahu Tongariki lies another must-see site: the volcanic crater Rano Raraku, from which the rock used to create almost all of the moai was derived. Smooth walking paths meander through the crater’s quarries and among nearly 400 statues in various stages of development that were never transported to their ahus.

The path through the Rano Raraku quarry winds past dozens of moai that were carved but never transported to ahus. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Anakena, Easter Island's only sand beach, is a great place to relax and ponder the island's many enigmas. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

“Detailed geochemical analyses have revealed that the islanders carefully selected and carved only the strongest and lightest stone found on the island. Whereas other rocks were too heavy, too loose or too brittle, Rano Raraku’s light gray, consolidated ash (called tuff) is relatively lightweight, strong and homogenous. These properties not only enabled the artisans to carve the enormous statues, but also made it more practical to transport them across the island. The craftsmen fashioned the pukao from reddish scoria derived from Puna Pau quarry, near Hanga Roa. This rock not only offers a striking color contrast with the gray moai, but is even less dense, thanks to its relatively high porosity, making it easier to hoist the topknots atop the moais' heads.

No one has determined exactly how the moai and their topknots were moved or erected atop the ahus. Many researchers favor the idea that the islanders cut down the once lush palm forest to logroll the statues, but others, including Hunt and Carl Lipo, an archaeologist at California State University-Long Beach, disagree. In 2011, the two scientists staged a demonstration in which teams of people successfully moved upright, comparably sized statues along dirt paths using only strong ropes — a claim that more closely corresponds to local Polynesian legends that the statues “walked” to their platforms.

Visitors to Rano Raraku’s quarry should also wander over to the western side of the crater to see the beautiful crater lake, surrounded by lush totora reeds. It was pollen in sediment cores collected from this lake that revealed the temporal changes in vegetation that have fueled the controversy over the cause of the island’s ecosystem collapse, which coincided with the abandonment of the quarry.

Rise of the Birdman Cult

Visitors can hike or drive to the rim of the stunning Rano Kau crater. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

“A drive up to the rim of Rano Kau crater at the island’s southwestern corner provides visitors with sweeping vistas down to another reed-covered crater lake and out over the sea to two craggy islets that figure prominently in the “birdman” cult, which became the focus of local religious life following the decline of the ancestral worship associated with the moai. Cult activities revolved around an annual competition to collect the season’s first sooty tern egg from an islet 2 kilometers offshore.

Contestants prepared themselves in Orongo Village for the annual competition associated with the birdman cult. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

Competitors prepared themselves for the rigorous trial in the ceremonial village of Orongo where nearly 50 boat-shaped, stone-slab structures perch on a narrow ridge between the deep crater and precipitous sea cliffs. When ready, competitors climbed down the cliffs, made the treacherous swim across to the islet, and then waited for the terns to arrive. Many competitors died during the endeavor, but whoever found the first egg and returned it safely to the village was declared that year’s winner and was entitled to a number of tributes as well as the right to spend a year just sleeping and eating. The cult endured until the mid-1800s, when Christian missionaries suppressed it.

Not Your Typical South Pacific Vacation

Birdman cult contestants had to swim to an offshore islet to retrieve the season's first sooty tern egg. Credit: Terri Cook and Lon Abbott.

'Wonderful World' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 거인군단 모아이가 지키는 이스터섬(Easter Island) (1) | 2024.10.20 |

|---|---|

| Easter Island Rapa Nui in Chile (1) | 2024.10.20 |

| Cowiche Canyon Preserve — Washington Trails … (0) | 2024.10.20 |

| San Juan, the capital and largest city of the Argentine province of San Juan (1) | 2024.10.20 |

| Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore (0) | 2024.10.20 |